The Victoria Hall Disaster

“Soon men began to come down the steps bearing in their arms lifeless burdens, and from the crowd came a wail of grief…”

William Codling 1894

Victoria Hall a Victorian-gothic style brick building, built in 1872, located in Sunderland England. Would soon be the location of a of not only “the greatest treat for children ever given,” but also “the greatest tragedy”.

Shortly after 5pm on Saturday June 16th, 1883. The excitement and joy that had filled Victoria Hall with the sound of laughter and applause, would soon be overshadowed, by the sound of panic, wailing, and grief. In mere seconds the lives of hundreds of families and kids would be forever changed.

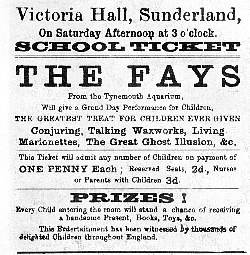

Alexander Fay – the conjurer- and his sister Annie Fay – the enchantress – had been touring “Fays Wonders” around the world. They were even the resident performers at the Tynemouth Aquarium in Northeast England. They had planned a show filled with conjuring, talking waxworks, living marionettes and ghost illusions.

The Fays had come into town a few weeks early to prepare not only for the show but also to try to push ticket says. They had even been seen in the rain handing flyers and, in the school, offering free tickets to teachers and staff if they would help sell tickets. The price of a ticket was only 1 penny, and for children living in such an impoverish community, this was a welcomed “treat”. Of course, the price wasn’t the only thing too good to be true, The Fays had also promised “every child in the room will stand the chance of receiving a handsome present, books, toys, etc.” What little boy or girl wouldn’t be enticed by the promise of a chance to receive a free toy?

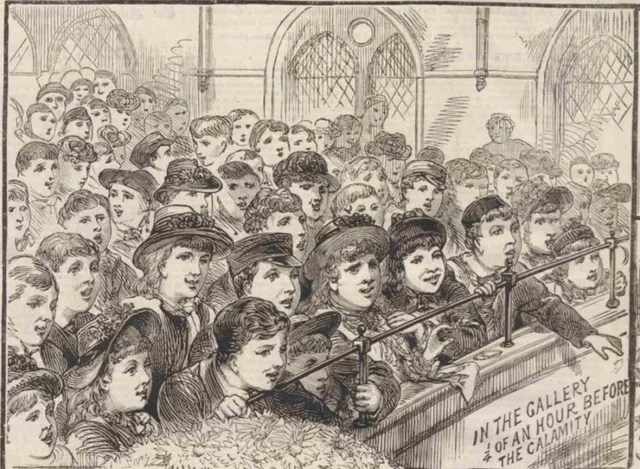

The day of the show as almost 2000 seats were filled by a crowd of mainly three to 14-year-old children and teens, 1000 of which would be seated in one of the two upper galleries in Victoria Hall.

The Hall went quiet as all 2000 children watched as the Fays started the show. The show would continue without any problems, that is until the last act of the night, in an instant the stage was filled with smoke. It had quickly made its way to the front few rows of the auditorium. Some of the children began to feel sick, a few even ended up vomiting from the smoke. Alexander Fay saw this and quickly tried to bring the focus back to himself in an attempt to control the crowd.

He quickly called out the numbers of the tickets that had won prizes, informing the children that one of their assistants would be making his way to the top galleries to pass out prizes. The assistant would be delayed, and the kids upstairs would begin to grow impatient at the thought that they were missing out on the toys.

Several things would contribute to the calamity that would ensue in the following moments. The lack of parental supervision, lack of coordination, the impatient attitudes of the children, and lack of safety regulations at the time, would all add themselves to the “conjuring” of this great disaster.

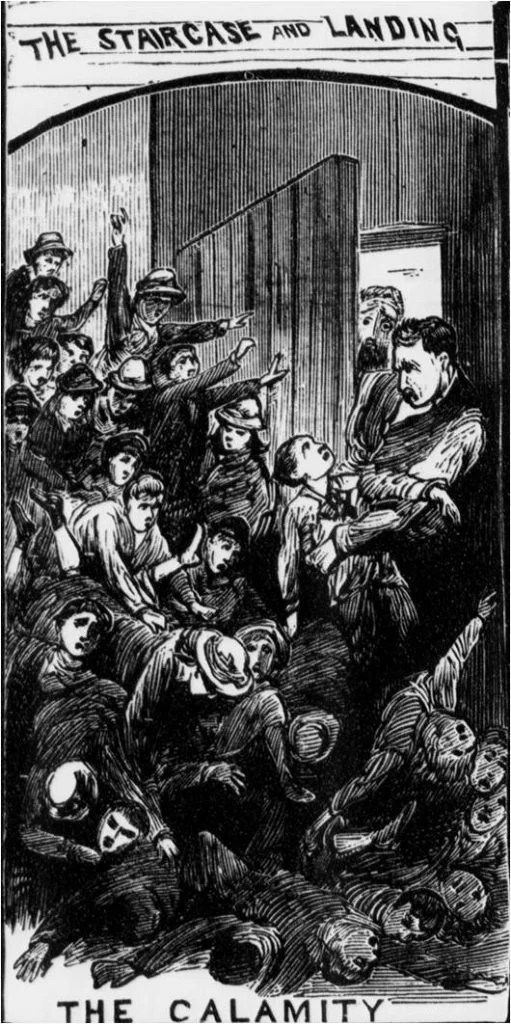

In moments a horde of children would leave their seat, “en mass” and make their way to the closest stairway. What would start as a stampede, would soon become a congested traffic jam of children, crammed shoulder to shoulder, and almost hypnotically moving forward.

The children kept moving forward, fixated on the idea of “free toys,” without any other concern or thought. They were deaf to the sounds of children screaming, “STOP, KEEP BACK!” The children were just as unaware of what was really happening, as the few adults in attendance were.

During the excitement, and rush to get to the toys, one child tripped and fell at the bottom of the stairs. In front of a door that not only opened inward, but had been bolted open, with only a 20-inch gap. Enough room to allow for one child at a time to pass throw, no doubt in an attempt to make ticket counting easier. This 20-inch gap, and the fact that no one had bothered unbolting the door after the show had started, helped to cause an almost domino effect. Other children soon started tripping over the first, and with the children behind not knowing or not paying attention, the mass kept coming.

William codling would give an account of what happened 11 years later 1894, he was around six or seven when it happened.

“The conjurer performed his tricks and at the close of the entertainment stepped to the front of the stage with a basket of toys and began throwing them among the people in the pit. We in the gallery howled with rage. At this the conjurer informed us that a man was already on his way up the stairs with a basket of toys for us. So, we obligingly rose en masse and went down the stairs to meet him.

I raced up the gallery as fast as I could, scrambled with the crowd through the doorway and jolted my way down two flights of stairs. Here the crowd was so compressed that there was no more racing, but we moved forward together, shoulder to shoulder. Soon we were most uncomfortably packed but still going down.

Suddenly I felt that I was treading upon someone lying on the stairs and I cried in horror to those behind “Keep back, keep back! There’s someone down.” It was no use, I passed slowly over and onwards with the mass and before long I passed over others without emotion.”

Eventually a few of the adults noticed that something was not right. The adults rushed to the door which was now piled about 6-feet high with the bodies of children. The adults quickly tried to move the door but could not undo the bolt and the pressure of children now pushing agaimst it made it even more challenging. Two adults ran up a second stair case which was used as an auxiliary stair case to relieve congestion, but was not open at the time.

They started to yell to the children that toys were being distributed in another area, the children snapped out of their mass trance and started to follow the two men. The pressure lessened but it was too late.

Mr. Fay was none the wiser to what was going on. Mr. Fays account at the inquest was this.

“The first mention I had of the accident was Hesseltine. He came to the body of the hall.

[Question:]—How did he come ?

He did not rush ; he came slowly, and fell on his back on the stairs. He seemed in a fainting condition… I pulled him, but he did not answer, and I then threw some water in his face. He presently came around, and I asked him what was the matter. He said, “Oh dear, there’s some of them stuck fast, and they are dead.” I asked how many, and he mentioned the word “dozen.”

“Oh dear, there’s some of them stuck fast, and they are dead.” I asked how many, and he mentioned the word “dozen.”

Alexander Fay retelling his account of the disaster

I left him and rushed to the pit entrance. I then saw two or three men running about, and I noticed two or three little boys lying on their backs at the pit entrance, and a man with another in his arms. I picked them up. I was very much excited, and said to a man, “Are they dead?” He said, ” Yes ; there are a good many more dead. Run for a doctor.”

[Question:]—Did you know then what had occurred ?

No.”

Dr. Lambert, who lived close to Victoria Hall was the first to arrive. He was immediately told that one boy was “in a fit or dying.”

Dr. Lamber would later recount to the court his account of what happened.

“ I quickly ascended the steps, and soon came to the body of the child. I found the little fellow was quite dead, and from appearances, such as intense congestion and puffiness of the face, looking purple or blackish, turgid vessels in the neck, bloody froth from the nose, as also bloody discharge from the ears, I came to the conclusion that death had resulted from suffocation. There was no one near the body who could give me any information whatever.

A sudden presentiment that a mortal struggle was going on at a certain situation leading from the gallery, caused me to run up the flight of stairs, at the top of which is a landing. Turning round a corner in the gallery-stairs proper, I beheld the dark, horrible pit of destruction, with three hundred or more children in it ; and, oh ! shocking sight ! a heap, most of whom appeared to be dead, so feeble were the groans and cries (for they could not get breath to cry) of the living. Hence no one could believe that a few yards from the spot actually more than a hundred were already dead. It may be safely asserted that within five minutes of the block taking place at least this number would be dead.

Through the eighteen-inch space that the door was open I could see the hall-keeper making almost superhuman efforts, with others, to release the fatal door, but to no avail.”

“Many of the children on the outer edge of the frightful heap could be made out to be past human aid. They had fallen early in the frightful struggle, and those who came after had been precipitated over them in the far side of the heap. In order to get at the latter, hands had to be joined by the rescuers so that one might reach over the nearer bodies and take hold of some little one whose feeble movement gave sign that life was not extinct… What seemed to wring the hearts of the rescuers with the utmost anguish were the cries of those who were able to cry. It was, “Give me a hand !” “And give me a hand !” “Oh ! Do take me out first !” or “Oh ! Where is my mother !””

William Codling, one of the children who had survived would continue his account.

“I had not thought the affair was serious and now I looked on spellbound as body after body was brought out and laid in a row upon the pavement. One woman, I remember, came out carrying a child which she had gone in to seek while behind her came a sympathetic man bearing another.

The woman came down the steps with agonised face and dishevelled hair and shouted fiercely to the crowd “Get back! Get back! And let them have air.”

“Ah! my good woman,” said the man who bore her other burden, while tears rolled down his cheeks, “Ah! they will never need air more.”

Soon men began to come down the steps bearing in their arms lifeless burdens, and from the crowd came a wail of grief…”

William Codling

“Then the pressure began to lessen,” Codling said. “A report spread that the toys were being distributed in the gallery and those behind having made a feeble rush upwards, back we tottered across that path of death. … At the first landing we were met by some men and taken out of doors into the open air…Soon men began to come down the steps bearing in their arms lifeless burdens, and from the crowd came a wail of grief…”

183 kids died that day. Some parents lost all of their kids in the disaster, among those lost was an entire Sunday school class. Queen Victoria sent a message of condolences and contributed to the Disaster Fund. Donation from all over England came in totaling over 5,000 pounds (adjusted for inflation in dollars equals 646,337.92 dollars).

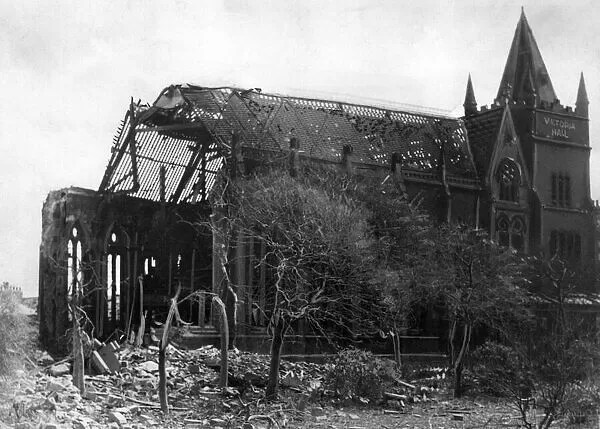

Victoria Hall would stand for another 58 years before sustaining substantial during an air raid in 1941.

A statue of a weeping woman holding a dead child was erected after the tragedy. It was later restored and moved to Mowbray Park where it stands now as a testament to one of the most horrific disasters to happen in Britain.

Legislation would lead to new requirements that would call for more outwards opening exits in venues. The events would be the catalyst for Robert Alexander Briggs to invent the push bar. A door that can be locked from the outside but will always open from the inside. Though legislation was passed it wasn’t globally copied, so more events would happen before it was accepted world wide. Which lead to at least 602 people dying in the Iroquois Theater Fire in Chicago in December 1903 because of door latch designs that were difficult for fleeing patrons to open